On Tuesday, an FIR was registered against lawyers who attempted to prevent the police from filing charge sheet in the Kathua rape and murder case in Jammu and Kashmir, as the investigation came close to a conclusion.

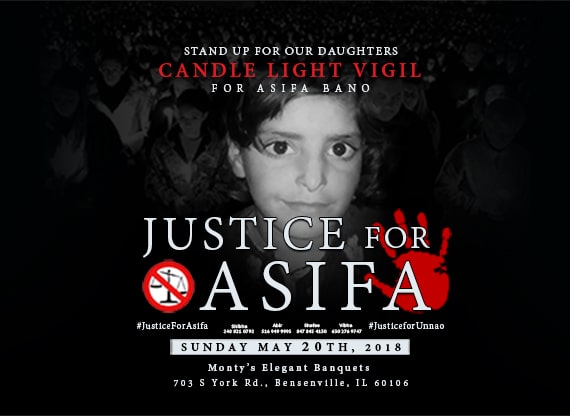

She was an eight-year-old girl, who, while grazing her horses in a meadow in northern India in January, followed a man into the forest. Days later, Asifa Bano’s small, lifeless body was recovered there.

Police say that Asifa was given sedatives and for three days, raped several times by different men. Asifa was eventually strangled on 17 January, something police say would have happened sooner had one man not insisted on waiting, so that he could rape her a final time.

To ensure she was dead, Asifa’s killers hit her twice on the head with a stone, according to charging documents filed by police in the state of Jammu and Kashmir and published by the Indian news website Firstpost.

In the months since, Asifa’s death has brought anguish to Kathua, the small town where she was killed. But it’s also brought division. Asifa’s case is the latest example of India’s religious friction: as some denounce sexual violence and demand justice for Asifa’s family, others demand justice for the men accused.

The eight men accused of raping and killing Asifa are Hindu. Asifa was a Muslim nomad, part of the Bakarwal tribe. Asifa’s father, Mohammad Yusuf Pujwala, told The New York Times that he believes his daughter was killed by the Hindu men for the sole purpose of driving her people away. To add to the volatility of Asifa’s case, police say she was killed in a Hindu temple and that the temple’s custodian plotted her death as a way to torment the Bakarwals.

Asifa was the pawn. “A child of only eight years of age who … became a soft target,” police said.

On Monday, a chaotic scene unfolded outside a courthouse in Jammu and Kashmir, as a mob of Hindu attorneys tried to physically stop police from filing charges against the men accused. The attorneys in a statement argued for a federal investigation, stating that the government had failed to “understand the sentiments of the people”. Police still managed to complete the paperwork and charged the men, who include four policemen and a retired government official.

Protests have now spread across much of Kathua. Hindu activists argue that some of the police officers who worked on the case are, like Asifa, Muslims – and cannot be trusted, according to The New York Times. Dozens of Hindu women have helped block a highway and organise a hunger strike.

“They are against our religion,” Bimla Devi, a protester, told The New York Times. She said that if the accused men weren’t freed, “we will burn ourselves”.

The lawyers, along with a group affiliated with India’s ruling Hindu nationalist Bharatiya Janta Party (BJP), fight on the basis of religious prejudice, even though BJP supporters are vocal opponents of sexual violence. After the brutal gang rape and murder of a medical student in New Delhi in 2012, the government promised to introduce legal reforms and support services to help victims of sexual violence. To an extent, it did – for example, the government amended the law to prosecute children older than 16 as adults in rape and murder cases. (Not much more has changed for rape victims, however, according to a November report by Human Rights Watch).

Notable BJP members have asked the case be moved out of the state police’s jurisdiction and into that of the Central Bureau of Investigation, claiming the agency would act neutrally. The Central Bureau of Investigation, however, reports to the BJP-led government in New Delhi.

Asifa’s case has shaken the state’s Legislative Assembly. Weeks after her body was found, lawmakers still questioned the police’s behaviour in the days after Asifa disappeared: police waited two days to file a report after Asifa disappeared, for example and did not alert newspapers until days after she was killed, according to the Asia Times.

“The screams and cries of the girl were heard by neighbours. Why was there such a delay by police [to help her?]” lawmaker Shamima Firdous said a few weeks after Asifa’s body was found, according to the Asia Times.

Talib Hussain, a Bakarwal social activist fighting on behalf of Asifa’s family, told The New York Times that Bakarwal nomads for generations have leased land from Hindu farmers so that their animals can graze during the winter. In recent years, however, Hindus in the Kathua area have campaigned against the nomads. Believed to be at the campaign’s helm is the accused custodian, Sanji Ram.

“His poison has been spreading,” Mr Hussain told The New York Times. “When I was young, I remember the fear Sanji Ram’s name invoked in Muslim women. If they wanted to scare each other, they would take Sanji Ram’s name, since he was known to misbehave with Bakarwal women.”

Mr Hussain could not be immediately reached for comment by The Washington Post.

Feelings of suspicion and animosity between the two communities run so deep that when Asifa didn’t return from the meadow, her parents instantly feared she’d encountered danger. And when the Bakarwal nomads retrieved Asifa’s body for her burial, “some baton-wielding goons appeared at the graveyard asking us not to bury her there,” Mr Hussain told the Asia Times.

The “goons,” he said, feared that if Asifa was buried on their land, it would forever belong to Muslims.